|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A photograph originally snapped with a Minolta 35mm camera. Looking east across what many paleontology enthusiasts call Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. All rocks in immediate view, excluding mountains on skyline of course, belong to the notably fossiliferous lower Cambrian Harkless Formation--which here happens to yield an extraordinary association of early invertebrate animal remains some 515 to 510 million years old--among them, locally common perfect trilobite carapaces. Supplemental exposures of such iconic geologic rocks units as the lower Cambrian Mule Spring Limestone, the lower to middle Cambrian Emigrant Formation, and the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation at Extinction Canyon--and in the general vicinity of the canyon's corridor--produce a prodigious invertebrate fossil fauna, including: algae (circular to oval nodules precipitated by an extinct variety of blue-green algae called Girvanella); Agmata (an extinct phylum that includes the so-called "ice cream cone fossil," salterella); archaeocyathids (an extinct calcareous sponge); brachiopods; Caryocaris (an extinct bivalve crustacean); corals (an extinct tabulate-type cnidarian); hyolithids (an extinct, formerly enigmatic critter historically considered either a mollusk or a member of own distinct phylum--but now definitively identified as an early lophophoroate, tangentially related to brachiopods, bryozoans, and phoronid annelids); Lidaconus (an extinct tusk-shaped small shelly fossil of unestablished zoological affinity); mollusks; glass sponges; and numerous species trilobites--including a number of perfect and mostly complete exoskeletons. Harkless Formation outcrop on low ridge at middle right foreground yielded plentiful well preserved Lidaconus specimens, weathered in aesthetically pleasing relief along the surfaces of slightly metamorphosed siltstones. |

|

Extinction Canyon in Nevada's Great Basin Desert physiographic province is indubitably positioned within the pantheon of sensational early Paleozoic Era paleontological localities in North America. It's an amazingly productive area where several varieties of long-vanished early Earth organisms, some of which left no discernible traces of modern descendants, now lie preserved in lower Cambrian to middle Ordovician rocks approximately 515 to 475 million years old, providing scientifically invaluable evidence of their final struggle to survive before eventually dying out. Not only that, but the area also just happens to produce rather common whole and mostly complete early Cambrian trilobites, a geologically spectacular preservational phenomenon that increases with compounded exponential power the locality's paleontological significance. As a matter of fact, I delayed writing about what many fossil-minded folks call Extinction Canyon until the professional paleontologists directly involved in important trilobite studies there had finally published their findings in peer-reviewed scientific publications. Invertebrate animala that left documented evidence of their literal last stands on Earth in the sedimentary rocks at Extinction Canyon include: archaeocyathids--an early calcareous sponge that never lived beyond late early Cambrian times; Caryocaris--a genus of bivalve crustacean confined worldwide to strata of lower to lower-middle Ordovician age; salterella--an enigmatic, diminutive conical critter, the so-called ice-cream cone fossil, assigned to its own unique phylum called Agmata, a phylum that never survived beyond late early Cambrian times; Lidaconus--a diminutive tusk-shaped shelly organism of unestablished zoological affinity that superficially resembles salterella, but is in fact not related to salterella--it too went belly-up not long before the conclusion of the Cambrian Period; and Olenellid trilobites (the earliest successful group of trilobites)--which disappeared quite abruptly near the conclusion of the early Cambrian some 510 million years ago. Also occurring in the local geologic column are examples of long-extinct creatures that elsewhere in North America left evidence of their terminal residence on Earth in rocks younger than the strata exposed in Extinction Canyon: Girvanella--disappeared during the latest Cretaceous Period about 66 million years ago, a genus of photosynthesizing cyanobacterial blue green algae that precipitated distinctive circular to oval nodule-like bodies now preserved in carbonate strata; hyolithids--a once-enigmatic conical invertebrate animal (which lived from early Cambrian to late Permian)--long considered some kind of mollusk, or even deserving of its own unique phylum, but now conclusively identified as an early lophophorate, related to Brachiopoda, Bryozoa, and possibly Phoronida; a tabulate coral, an order of cnidarian that disappeared from the geologic record during the end-time Permian Period mass extinction of some 252 million years ago; graptolites--generally agreed to represent an early hemichordate, a primitive vertebrate with a notochord instead of a fully calcified backbone, that died out in the late Mississippian Period (by the way, I reject outright the year 2012 claim that the living pterobranch Rhabdopleura is an extant graptolite--there is no evidence in my view that the graptolite was actually a pterobranch to begin with); and the trilobite orders Ptychopariida and Corynexochida, which went extinct during the late Ordovician and late Devonian, respectively. In addition to the organisms that went belly-up, extinct, other invertebrate animal groups preserved within Extinction Canyon and several additional geologic sections exposed not far from Extinction Canyon that actually survive to this date include brachiopods, mollusks, echinoderms, bryozoans, and glass sponges. At last field check, the general region many paleontology aficionados colloquially call Extinction Canyon, Great Basin environs, Nevada, still exists on land federally administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM)--AKA, public lands, where hobby collecting of reasonable amounts of common invertebrate fossils (including the trilobites) is allowed without the need of a formal special permit; of course, such paleontological remains must never be sold or bartered (legal argot that denotes trading of specimens), and all collecting must be done by hand. Mechanized excavations of fossilferous geologic strata here would constitue an obvious illegality. Here is a list of all trilobite species currently recognized not only from Extinction Canyon, exclusively, but also several geologically correlative neighboring early Paleozoic stratigraphic sections: 1) From the lowermost part of the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation (Waucoban Series, mid-Dyeran Stage): Olenellus sp. A; Ovatoryctocara yaxiensis; Protoryctocephalus arcticus; Oryctocephalops frishenfeldi; Anabocephalus silverpeakensis; Ogygopsis sp.; Coenoides scholteni; Harklessaspis rasettii; Bonnia brennus; Olenellus sp. B; 2) From the middle and upper sections of the lower Cambrian Harkless Formatioin (Waucoban Series, mid-Dyeran Stage): Harklessaspis parvigranulosis; Olenellus glabrum; Bonnia columbensis; Arcuolenellus megafrontalis; Arcuolenellus arcuatus; Zacanthopsis sp.; Zacanthopsis levis; Bristolia mohavensis; Crassifimbra sp. B; Crassifimbra sp. A; Bristolia harringtoni; Proliostractus sp.; Olenellus transitans; Bonnia sp.; Ogygopsis marconi; Zacanthopsis contractus; Lancastria roddyi; Olenellus sp.; Protypus inflatus; Cheiruroides sp.; Olenellus thompsoni. 3) From the lower part of the lower Cambrian Mule Spring Limestone (Waucoba Series-upper Dyeran Stage): Bristolia harringtoni; Bristolia insolens; "Ptychoparioid" sp. D; Bristolia bristolensis; Bristolia anteros; "Ptychoparioid" sp. A; Bristolia fragilis; "Ptychoparioid" sp. C; Bonnia sp. 4) From the upper section of the lower Cambrian Mule Spring Limestone (Waucoba Series-upper Dyeran Stage): Olenellus puertoblancoensis; Crassifimbra walcotti; Olenellus gilberti; Cornyexochid; Bolbonellus brevispinus; Zacanthospsis "levis"; Kochaspid? sp.; "Ptychoparioid" sp. B; Bathynotus sp. 5) From the lower part of the middle Cambrian Emigrant Formtion (Lincolnian Series, Delamaran Stage): Eokochaspis nodosa; Amecephalus arrojoensis; Oryctocephalus indicus; Onchocephalites claytonensis; Kootenia sp.; Pagetia aspinosa; Achlysopsis brighamensis; Chancia maladensis; Pentagnostus bonnerensis; Pentagnostus brighamensis; Syspacephalus mccollumorum; Achlysopsis brighamensis; Glossopleura walcotti; Zacanthoides sp.; Oryctocephalites sp; Kistocare sp.; Pagetia fossula; Pagetia rugosa; ptychopariid; Zacanthoides cf. Z. longipygus; Pagetia claytonensis; Alokistocare cf. A. paranotatum; Bathyuriscus terranovensis; Elrathina marginalis; Oryctocephalus cf. O. reynoldsi; Parkaspis cf. P. drumensis; Thoracocare cf. T. minuta; Zacanthoides divergens; Elrathina? wheelera; Cedaria selwyni; Coosella sp.; Crepicephalus sp.; Meteoraspis sp.; Tricrepicephalus sp.; Agnostoid sp.; Cedaria cf. C. brevifrons; Utia curio?; Cedaria selwyni,; Cedaria sp. 1; Cedaria sp. 2; Coosia sp. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left: A Google Earth street car perspective that I edited and processed through photoshop. The journey to Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada, begins here--requiring considerable travel along semi-maintained dirt roads and primitive trails through classic uninhabited Great Basin Desert terrain. This is a spectacularly isolated area; no immediate emergency medical or mechanical assistance is available. To safely access all places of paleontological significance at Extinction Canyon, one must employ a reliable four-wheel drive vehicle. Right: A photograph originally snapped with a Minolta 35mm camera. An enthusiast of early Paleozoic Era paleontology at camp during late afternoon along the flatlands near the mouth of Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left: A photograph originally snapped with a Minolta 35mm camera. A cholla cactus, backlit by late afternoon sunlight near the mouth of Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Right: A photograph originally snapped with a Minolta 35mm camera. Seekers of early Paleozoic Era paleontology explore a dry wash along the western side of Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. The view is roughly eastward. Slope directly behind the CJ7 jeep yielded numerous nicely preserved Salterella specimens--a diminutive, extinct ice cream cone-shaped invertebrate animal that paleontologists assign to a unique phylum called Agmata--from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation. |

|

|

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A photograph originally snapped with a Nikon 35mm camera. A view westward along a ridgeline in the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, near its geologic contact with the overlying lower Cambrian Mule Spring Limestone (just out of site). Slabs of shale at bottom foreground mark a major trilobite quarry in the Harkless Formation, which here produces significant specimens of the genera Olenellus, Ogygopsis, Bonnia, and Proliostractus (among many other genera, as well)--including not a few complete exoskeletons. Stratigraphically older Harkless rocks exposed behind the whitish layer at lower left to upper right preserve the last archaeocyathids (calcareous sponge) and salterella (Phylum Agmata) in the geologic record, just prior to their extinction. Within the overlying lower Cambrian Mule Spring Limestone (younger than the Harkless Formation), the Olenellid trilobites go extinct, as well. Right: A photograph originally snapped with a Minolta 35mm camera. An adventurer of early Paleozoic paleontology heads eastward, back to the main road through Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada, after exploring a world-class Caryocaris crustacean locality in the lower Ordovician portion of the Palmetto Formation exposed on the western flanks of Extinction Canyon. Caryocaris is an extinct phyllocarid arthropod whose oval to D-shaped bivalved remains are restricted worldwide to graptolitic shale facies of lower to middle Ordovician geologic age. An anomalous Caryocaris crustacean occurrence described from late Ordovician strata in Denmark must indeed be genuinely considered a controversial stratigraphic outlier. Dirt road in distance passes through the graptolite, brachiopod, and Caryocaris-bearing lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation. Ridge at far upper right is composed of the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation (lower slopes), lower Cambrian Mule Spring Limestone (darker material at top of ridge), and the middle Cambrian Emigrant Formation (exposed primarily on eastern side of the ridge, out of sight). |

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for a larger pictures. Left: A photograph originally snapped with a Minolta 35mm camera. Enthusiasts of early Cambrian and early to middle Ordovician paleontology are headed eastward, back to camp, after exploring at Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert Nevada, a specific world-famous locality in the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation that produces prodigious quantities of salterella (a diminutive, extinct, roughly ice cream cone-shaped paleotological remain assigned to its own unique phylum, called Agmata) and significant specimens of the trilobite genera Olenellus, Ogygopsis, Bonnia, and Proliostractus (among many other genera, as well) that are locally found as whole and mostly complete, exoskeletons. Within the overlying lower Cambrian Mule Spring Limestone, the Olenellid trilobites go extinct. Middle and far right: Photographs originally taken with a Nikon 35mm camera. Two views roughly northwestward from a world-famous trilobite quarry in the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada, near its geologic contact with the overlying lower Cambrian Mule Spring Limestone. Here, the Harkless produces significant trilobite specimens of the genera Olenellus, Ogygopsis, Bonnia, and Proliostractus (among many other genera, as well). Within the overlying lower Cambrian Mule Spring Limestone, the Olenellid trilobites go extinct. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left: A photograph originally snapped with a Minolta 35mm camera. A view westward in an archetypical dry desert wash along the western side of Extinction Canyon--returning to base camp (eastward, in the jeep) after successfully exploring a classic trilobite quarry in the youngest stratigraphic intervals of the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, a locality that produces not a few complete, whole, trilobite exoskeletons. Brownish rocks that border the wash to the immediate south of the jeep (left side of image), belong to the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, which here produces locally abundant excellently preserved Lidaconus specimens--a diminutive curved tusk-sha;ped shell whose living resident--of unestablished zoological affinity--went belly-up, extinct, at the close of the lower Cambrian Period roughly 509 million years ago. Right: A photograph originally snapped with a Nikon 35mm camera. An aficionado of Great Basin Desert exploration stands amidst an abandoned silver-lead mining camp at Extinction Canyon, Nevada. View is roughly northwestward. All rocks in immediate view belong to the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation, which here yields impressive quantities of graptolites, an extinct colonial organism that resembles the modern pterobranch, a hemichordate (primitive chordate, with a notochord instead of a mineralized skeletal spine). |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right: Photographs originally snapped with a Nikon 35mm camera. A seeker of paleontological adventure explores outcrops of graptolite-bearing shale and siltstone in the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Viewing perspective is southward. Graptolites represent an extinct colonial organism of worldwide distribution that resemble the modern pterobranch, a hemichordate (primitive chordate, with a notochord instead of a mineralized skeletal spine); they reached their ultimate speciation development and adaptive diversification during the Ordovician Period, roughly 485 to 444 million years ago. All rocks within view belong to the Palmetto Formation. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Photograph originally snapped with a Nikon 35mm camera. A seeker of paleontological adventure explores outcrops of graptolite-bearing shale and siltstone in the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Viewing perspective is southward. Graptolites represent an extinct colonial organism of worldwide distribution that resemble the modern pterobranch, a hemichordate (primitive chordate, with a notochord instead of a mineralized skeletal spine); they reached their ultimate speciation development and adaptive diversification during the Ordovician Period, roughly 485 to 444 million years ago. All rocks within view belong to the Palmetto Formation. Right--Photograph originally taken with a Minolta 35mm camera. A view looking slightly south of due east across Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada, to a ridge composed primarily of the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

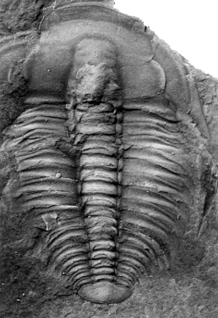

Click on the image for a larger picture. A mostly complete undescribed trilobite--order Ptychopariida--from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A mostly complete undescribed trilobite--order Ptychopariida--from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A mostly complete undescribed trilobite--order Ptychopariida--from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Curvature of axial ring ("spine") likely caused by postmortem deformation. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A mostly complete trilobite of an unspecified ptychopariid trilobite from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A mostly complete trilobite--family Dorypygidae --from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Called scientifically, genus Ogygopsis. Students of Cambrian paleontology might recognize the name Ogygopsis from its occurrence in the world-famous middle Cambrian Burgess Shale, Canada, where it is by far the most abundant fossil represented in the spectacular fossil deposit, noted for its plentiful soft-bodied preservations. Photograph courtesy a specific web page. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A mostly complete unspecified trilobite from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Photograph from a specific web page. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A mostly complete trilobite from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Called scientifically, genus Bonnia. Photograph from a specific web page. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A mostly complete trilobite (upper left), with two pygidia and two cephalons on the same bedding plane, from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Called scientifically, genus Bonnia. Photograph from a specific web page. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A complete trilobite from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Called scientifically, genus Ogygopsis. Students of Cambrian paleontology might recognize the name Ogygopsis from its occurrence in the world-famous middle Cambrian Burgess Shale, Canada, where it is by far the most abundant fossil represented in the spectacular fossil deposit, noted for its plentiful soft-bodied preservations. Photograph courtesy an individual who goes by the cyber-name, paul7. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A complete trilobite and a cephalon (head shield) from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. An unspecified ptychopariid. Photograph from a specific web page. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A complete trilobite from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Called scientifically, genus Proliostracus. Photograph from a specific web page. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A complete trilobite from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Called scientifically, genus Proliostracus. Photograph from a specific web page. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A complete trilobite from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Called scientifically, genus Proliostracus. Isolated cephalons (head shields) preserved along the same bedding plane, as well. Photograph from a specific web page. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Two roughly three-quarters complete Ptychopariida trilobites (their pygidia are missing) lying side by side on a slab of slightly metamorphosed shale from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A cephalon (head shield) of an olenellid trilobite called Olenellus sp. from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Extinction Canyon is a particularly excellent area in which to observe the moment in geologic time when the olenellid trilobites died out. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A cephalon (head shield) of an olenellid trilobite called Olenellus sp. from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Extinction Canyon is a particularly excellent area in which to observe the moment in geologic time when the olenellid trilobites died out. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Two pygidia (tail sections) of unspecified ptychopariid trilobites on the same bedding plane, from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A pygidium (tail-hind section) of an unspecified ptychopariid trilobite from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A cephalon (head shield) of an unspecified ptychopariid trilobite from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A mostly complete trilobite from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Called scientifically, Ovatoryctocara cf. yaxiensis. Note that the cephalon is partially detached from the thorax. Photograph courtesy Frederick A. Sundberg and Mark Webster. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. An olenellid trilobite cephalon (head shield) from the lower Cambrian Mule Spring Limestone, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Called scientifically Olenellus (Paedeumias) puertoblancoensis. One of the last olenellid trilobites to exist; from a stratigraphic interval in the lower Mule Spring Limestone immediately above which (in younger rocks) all olenellid trilobites permanently disappear from the geologic record during the latest early Cambrian Period some 509 million years ago. Photograph courtesy Frederick A. Sundberg and Mark Webster. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A mostly complete trilobite from the middle Cambrian Emigrant Formation, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Not collected in Extinction Canyon, but occurs in stratigraphically correlative Emigrant Formation exposures situated in the general neighborhood of Extinction Canyon. Called scientifically Onchocephalites claytonensis. Photograph courtesy Frederick A. Sundberg and Linda B. McCollum.

|

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A mostly complete trilobite from the middle Cambrian Emigrant Formation, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Not collected in Extinction Canyon, but occurs in stratigraphically correlative Emigrant Formation exposures situated in the general neighborhood of Extinction Canyon. Called scientifically, Amecephalus arrojosensis. Photograph courtesy Frederick A. Sundberg and Linda B. McCollum. |

|

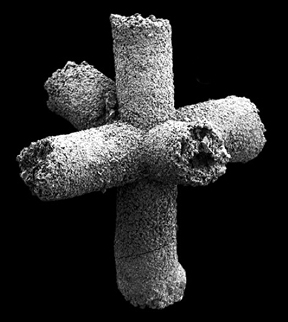

Click on the image for a larger picture. Salterella--an extinct invertebrate animal paleontologists place into its own unqique phylum, called Agmata--from the lower Cambrain Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Many Extinction Canyon paleontology aficionados colloquially call salterella "the ice cream cone fossil." Extinction Canyon is a particularly excellent area in which to observe the precise moment in geologic time when salterella died out; its last stand happened within the upper one-quarter (youngest phases of sedimentary deposition) of the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A closer look at a portion of the salterella-bearing specimen seen in the top image, directly above, from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Note the considerable concentration of the extinct invertebrate animal, placed by invertebrate paleontologists into its own unique phylum--called Agmata. Extinction Canyon is a particularly excellent area in which to observe the precise moment in geologic time when salterella died out; its last stand happened within the upper one-quarter (youngest phases of sedimentary deposition) of the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation. |

|

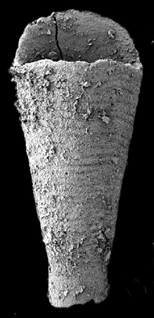

Click on the image for a larger picture. Curved tusk-like to ice cream cone-shaped Lidaconus specimens weather out in relief on a piece of slightly metamorphosed shale from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Lidaconus is an extinct invertebrate animal of unestablished zoological affinity. The critter never survived past the early Cambrian age. Extinction Canyon is a particularly excellent area in which to observe the precise moment in geologic time when Lidaconus died out; its last stand happened within the upper one-quarter (youngest phases of sedimentary deposition) of the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Curved tusk-like to ice cream cone-shaped Lidaconus specimens weather out in relief on a piece of slightly metamorphosed shale from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Lidaconus is an extinct invertebrate animal of unestablished zoological affinity. The critter never survived past the early Cambrian age. Extinction Canyon is a particularly excellent area in which to observe the precise moment in geologic time when Lidaconus died out; its last stand happened within the upper one-quarter (youngest phases of sedimentary deposition) of the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Lidaconus palmettoensis from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Great Basin Desert, Nevada; several specimens dissolved from of their limestone matrix with a diluted acid bath--an enigmatic conical, curved small shelly animal of unestablished zoological affinity. Specimens not collected from Extinction Canyon, proper, but from stratigraphically correlative strata not far from Extinction Canyon. The critter never survived past the early Cambrian age. Extinction Canyon is a particularly excellent area in which to observe the precise moment in geologic time when Lidaconus died out; its last stand happened within the upper one-quarter (youngest phases of sedimentary deposition) of the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation. Photograph courtesy Beth R. Onken and Philip W.Signor. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A natural cross-section of a relatively large archaeocyathid (an extinct variety of calcareous sponge) from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Extinction Canyon and a couple of additional localities in Nevada record the moment in geologic time when archaeocyathids died out during the late early Cambrian--their last stand happened in the uppermost (youngest) exposures of the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation. Photograph courtesy Elizabeth Miller. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Natural cross-section of a relatively large archaeocyathids (an extinct variety of calcareous sponge) from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation. Extinction Canyon records the moment in geologic time when archaeocyathids died out during the late early Cambrian--their last stand happened in the uppermost (youngest) exposures of the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation. Photograph courtesy Elizabeth Miller. |

|

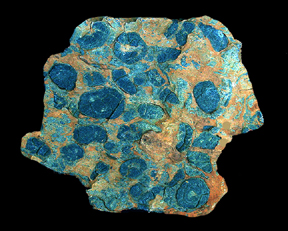

Click on the image for a larger picture. An extinct variety of photosynthesizing blue-green algae called genus Girvanella preserved as dark oval to circular nodule-like structures in the lower Cambrian Mule Spring Limestone, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

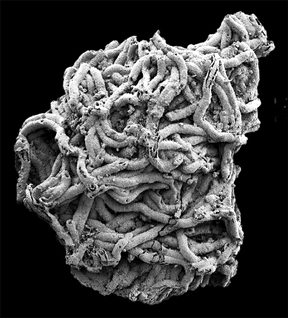

Click on the image for a larger picture. A mass of tangled Girvanella blue-green cyanobacterial filaments from the lower Cambrian section of the lower-middle Cambrian Emigrant Formation, from a locality not far from Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada; specimen is greatly magnified. The spaghetti-like strands constitute remains of the actual cyanobacterial algal growths. Photograph courtesy Chistian B. Skovsted. |

|

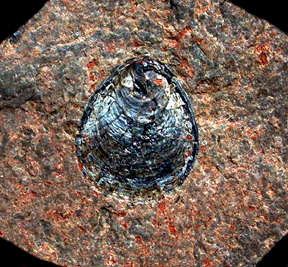

Click on the image for a larger picture. A brachiopod from the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. The specimen is preserved with its original lustrous phosphatic shell material intact. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A brachiopod from the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. The specimen is preserved with its original lustrous phosphatic shell material intact. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A slab of shale containing shells of an extinct bivalved phyllocarid crustacean called Caryocaris; original phosphatic shell material has been preserved intact. From the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A slab of shale containing shells of an extinct bivalved phyllocarid crustacean called Caryocaris; original phosphatic shell material has been preserved intact. From the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A closer look some Caryocaris crustaceans (extinct phyllocarid) preserved on the piece of shale seen in the top image, directly above. Note that the original phosphatic shell material has been preserved intact. From the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Carbonized Caryocaris crustaceans (extinct bivalved phyllocarid) preserved on a piece of shale from the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A rare complete, entire, Caryocaris crustacean (extinct bivalved phyllocarid)--preserved with both valves splayed open along the hinge line--from the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Specimen is preserved with its original phosphatic shell material intact. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A graptolite--an extinct colonial hemichordate that in general morphological aspect resembles the modern pterobranch--called genus Climacograptus from the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A graptolite, genus Climacograptus, from the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation, Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada that exhibits special exceptional preservation: It's a partially silicified example that reveals an indication of the graptolite's actual three-dimensional life-like aspect; the vast majority of graptolite preservations occur as flattened veneer-like films of the colonial hemichordate. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Two latex casts of graptolites from the lower to middle Ordovician Palmetto Formation, Great Basin Desert, Nevada, that have produced three dimensional life-like reconstructions of the specimens. Called scientifically Dicellograptus gurleyi. Not collected at Extinction Canyon, but in stratigraphically correlative exposures situated in the neighborhood of Extinction Canyon. Photograph courtesy Rueben J. Ross Jr. and William B. N. Berry. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A dendroid graptolite colony from the lower Ordovician Palmetto Formation, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Not collected at Extinction Canyon, but in stratigraphically correlative exposures situated in the neighborhood of Extinction Canyon. Photograph courtesy Ben Waggoner. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A glass sponge spicule (class Hexactinellida) dissolved out in its original three-dimensional aspect from the lower Cambrian section of the lower-middle Cambrian Emigrant Formation, from a locality not far from Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada; specimen is greatly magnified. Photograph courtesy Christian B. Skovsted. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. An extinct helcionelloid mollusk dissolved free from carbonate rocks in the lower Cambrian section of the lower-middle Cambrian Emigrant Formation, from a locality not far from Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Specimen is greatly magnified, called scientifically Costipelagiella nevadense. Possible zoological affinities with gastropods, cephalopods, and monoplacophorans has been postulated by numerous investigators; nevertheless, they remain enigmatic constituents of the early Cambrian "small shelly fossils" category. Photograph courtesy Christian B. Skovsted. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. An extinct lophophorate hyolithid dissolved free from carbonate rocks in the lower Cambrian section of the lower-middle Cambrian Emigrant Formation from locality not far from Extinction Canyon, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Specimen is greatly magnified, called scientifically genus Parkula. Zoological affinity to living lophophorate brachiopods, bryozoans, and phoronid annelids is definitively established. Still and all, they remain enigmatic early Cambrian constituents of a group of extinct organisms commonly grouped together as "small shelly fossils." Photograph courtesy Christian B. Skovsted. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. The darker-colored object on rock slab is one of the oldest true corals in the geologic record, called scientifically Harklessia yuenglingensis (class Anthozoa, subclass Zoantharia--probably a tabulate coral); from the lower Cambrian Harkless Formation, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Not collected at Extinction Canyon, but in stratigraphically correlative exposures situated in the neighborhood of Extinction Canyon. Photograph courtesy Melissa Hicks. |

|

The Acoustic Guitar Solitaire Of Inyo: A Cyber-CD: I play 30 covers of some of my favorite songs on an acoustic 6-string guitar; it's all free music. Beyond The Timberline--A Cyber-CD: I play 32 selections comprised of covers and original tunes on acoustic 6 and 12-string guitars; it's all free music. The Distant Path--A Cyber-CD: I play 32 acoustic guitar covers and original compositions; it's all free music. Inyo And Folks--A Musical History--A Quintuple Cyber-CD: My parents and I play 203 selections; it's all free music. Acoustic Stratigraphy--A Cyber-CD: I play 34 covers of some of my favorite songs on 6 and 12-string guitars; it's all free music. Back To Badwater--A Cyber-CD: I play 32 covers and original compositions on 6 and 12-string guitars; it's all free music. All Inyo All The Time: All six of my cyber-cds in one place (includes a quintuple cyber-cd box set); links to all of my solo acoustic guitar playing, in addition to selections my parents and I recorded during the Golden Age of our spontaneous, impromptu recording sessions. Includes an option to stream all 364 selectons; thirteen hours, seventeen minues and forty seconds of music (it's all free music). It's A Happening Thing--Music From The Year 1967: All songs that charted US Billboard Hot 100 (#1 to #100) and Bubbling Under (records that charted in positions #101 to #135) in 1967. Fossils In Death Valley National Park: A site dedicated to the paleontology, geology, and natural wonders of Death Valley National Park; lots of on-site photographs of scenic localities within the park; images of fossils specimens; links to many virtual field trips of fossil-bearing interest. Fossil Insects And Vertebrates On The Mojave Desert, California: Journey to two world-famous fossil sites in the middle Miocene Barstow Formation: one locality yields upwards of 50 species of fully three-dimensional, silicified freshwater insects, arachnids, and crustaceans that can be dissolved free and intact from calcareous concretions; a second Barstow Formation district provides vertebrate paleontologists with one of the greatest concentrations of Miocene mammal fossils yet recovered from North America--it's the type locality for the Bartovian State of the Miocene Epoch, 15.9 to 12.5 million years ago, with which all geologically time-equivalent rocks in North American are compared. A Visit To Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada: Take a virtual field trip to a Nevada locality that yields the most complete, diverse, fossil assemblage of terrestrial Miocene plants and animals known from North America--and perhaps the world, as well. Yields insects, leaves, seeds, conifer needles and twigs, flowering structures, pollens, petrified wood, diatoms, algal bodies, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, bird feathers, fish, gastropods, pelecypods (bivalves), and ostracods. Fossils At Red Rock Canyon State Park, California: Visit wildly colorful Red Rock Canyon State Park on California's northern Mojave Desert, approximately 130 miles north of Los Angeles--scene of innumerable Hollywood film productions and commercials over the years--where the Middle to Late Miocene (13 to 7 million years old) Dove Spring Formation, along with a classic deposit of petrified woods, yields one of the great terrestrial, land-deposited Miocene vertebrate fossil faunas in all the western United States. Late Pennsylvanian Fossils In Kansas: Travel to the midwestern plains to discover the classic late Pennsylvanian fossil wealth of Kansas--abundant, supremely well-preserved associations of such invertebrate animals as brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, echinoderms, fusulinids, mollusks (gastropods, pelecypods, cephalopods, scaphopods), and sponges; one of the great places on the planet to find fossils some 307 to 299 million years old. Fossil Plants Of The Ione Basin, California: Head to Amador County in the western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada to explore the fossil leaf-bearing Middle Eocene Ione Formation of the Ione Basin. This is a completely undescribed fossil flora from a geologically fascinating district that produces not only paleobotanically invaluable suites of fossil leaves, but also world-renowned commercial deposits of silica sand, high-grade kaolinite clay and the extraordinarily rare Montan Wax-rich lignites (a type of low grade coal). Ice Age Fossils At Santa Barbara, California--Journey to the famed So Cal coastal community of Santa Barbara (about a 100 miles north of Los Angeles) to explore one of the best marine Pleistocene invertebrate fossil-bearing areas on the west coast of the United States; that's where the middle Pleistocene Santa Barbara Formation yields nearly 400 species of pelecypod bivalve mollusks, gastropods, chitons, scaphopods, pteropods, brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, ostracods (minute bivalve crustaceans), worm tubes, and foraminifers. Trilobites In The Marble Mountains, Mojave Desert, California: Take a trip to the place that first inspired my life-long fascination and interest in fossils--the classic trilobite quarry in the Lower Cambrian Latham Shale, in the Marble Mountains of California's Mojave Desert. It's a special place, now included in the rather recently established Trilobite Wilderness, where some 21 species of ancient plants and animals have been found--including trilobites, an echinoderm, a coelenterate, mollusks, blue-green algae and brachiopods. Fossil Plants In The Neighborhood Of Reno, Nevada: Visit two famous fossil plant localities in the Great Basin Desert near Reno, Nevada--a place to find leaves, seeds, needles, foilage, and cones in the middle Miocene Pyramid and Chloropagus Formations, 15.6 and 14.8 to 13.3 million years old, respectively. Field Trip To The Alexander Hills Fossil District, Mojave Desert, California: Visit a locality outside the southern sector of Death Valley National Park to explore a paleontological wonderland that produces: Precambrian stromatolites over a billion years old; early skeletonized eukaryotic cells of testate amoebae over three-quarters of billion years old; early Cambrian trilobites, archaeocyathids, annelid trails, arthropod tracks, and echinoderm material; Pliocene-Pleistocene vertebrate and invertebrate faunas; and late middle Miocene camel tracks, petrified palm wood, petrified dicotlyedon wood, and permineralized grasses. Dinosaur-Age Fossil Leaves At Del Puerto Creek, California: Journey to the western edge of California's Great Central Valley to explore a classic fossil leaf locality in an upper Cretaceous section of the upper Cretaceous to Paleocene Moreno Formation; the plants you find there lived during the day of the dinosaur. Early Cambrian Fossils Of Westgard Pass, California: Visit the Westgard Pass area, a world-renowned geologic wonderland several miles east of Big Pine, California, in the neighboring White-Inyo Mountains, to examine one of the best places in the world to find archaeocyathids--an enigmatic invertebrate animal that went extinct some 510 million years ago, never surviving past the early Cambrian; also present there in rocks over a half billion years old are locally common trilobites, plus annelid and arthropod trails, and early echinoderms. Plant Fossils At The La Porte Hydraulic Gold Mine, California: Journey to a long-abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the neighborhood of La Porte, northern Sierra Nevada, California, to explore the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff, which yields some 43 species of Cenozoic plants, mainly a bounty of beautifully preserved leaves 34.2 million years old. A Visit To Ammonite Canyon, Nevada: Explore one of the best-exposed, most complete fossiliferous marine late Triassic through early Jurassic geologic sections in the world--a place where the important end-time Triassic mass extinction has been preserved in the paleontological record. Lots of key species of ammonites, brachiopods, corals, gastropods and pelecypods. Fossil Plants At The Chalk Bluff Hydraulic Gold Mine, California: Take a field trip to the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada, for leaves, seeds, flowering structures, and petrified wood from some 70 species of middle Eocene plants. Fossils In Millard County, Utah: Take virtual field trips to two world-famous fossil localities in Millard County, Utah--Wheeler Amphitheater in the trilobite-bearing middle Cambrian Wheeler Shale; and Fossil Mountain in the brachiopod-ostracod-gastropod-echinoderm-trilobite rich lower Ordovician Pogonip Group. Fossil Plants, Insects And Frogs In The Vicinity Of Virginia City, Nevada: Journey to a western Nevada badlands district near Virginia City and the Comstock Lode to discover a bonanza of paleontology in the late middle Miocene Coal Valley Formation. Paleozoic Era Fossils At Mazourka Canyon, Inyo County, California: Visit a productive Paleozoic Era fossil-bearing area near Independence, California--along the east side of California's Owens Valley, with the great Sierra Nevada as a dramatic backdrop--a paleontologically fascinating place that yields a great assortment of invertebrate animals. Late Triassic Ichthyosaur And Invertebrate Fossils In Nevada: Journey to two classic, world-famous fossil localities in the Upper Triassic Luning Formation of Nevada--Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park and Coral Reef Canyon. At Berlin-Ichthyosaur, observe in-situ the remains of several gigantic ichthyosaur skeletons preserved in a fossil quarry; then head out into the hills, outside the state park, to find plentiful pelecypods, gastropods, brachiopods and ammonoids. At Coral Reef Canyon, find an amazing abundance of corals, sponges, brachiopods, echinoids (sea urchins), pelecypods, gastropods, belemnites and ammonoids. Fossils From The Kettleman Hills, California: Visit one of California's premiere Pliocene-age (approximately 4.5 to 2.0 million years old) fossil localities--the Kettleman Hills, which lie along the western edge of California's Great Central Valley northwest of Bakersfield. This is where innumerable sand dollars, pectens, oysters, gastropods, "bulbous fish growths" and pelecypods occur in the Etchegoin, San Joaquin and Tulare Formations. Field Trip To The Kettleman Hills Fossil District, California: Take a virtual field trip to a classic site on the western side of California's Great Central Valley, roughly 80 miles northwest of Bakersfield, where several Pliocene-age (roughly 4.5 to 2 million years old) geologic rock formations yield a wealth of diverse, abundant fossil material--sand dollars, scallop shells, oysters, gastropods and "bulbous fish growths" (fossil bony tumors--found nowhere else, save the Kettleman Hills), among many other paleontological remains. A Visit To The Sharktooth Hill Bone Bed, Southern California: Travel to the dusty hills near Bakersfield, California, along the eastern side of the Great Central Valley in the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, to explore the world-famous Sharktooth Hill Bone Bed, a Middle Miocene marine deposit some 16 to 15 million years old that yields over a hundred species of sharks, rays, bony fishes, and sea mammals from a geologic rock formation called the Round Mountain Silt Member of the Temblor Formation; this is the most prolific marine, vertebrate fossil-bearing Middle Miocene deposit in the world. High Sierra Nevada Fossil Plants, Alpine County, California: Visit a remote fossil leaf and petrified wood locality in the Sierra Nevada, at an altitude over 8,600 feet, slightly above the local timberline, to find 7 million year-old specimens of cypress, Douglas-fir, White fir, evergreen live oak, and giant sequoia, among others. In Search Of Fossils In The Tin Mountain Limestone, California: Journey to the Death Valley area of Inyo County, California, to explore the highly fossiliferous Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone; visit three localities that provide easy access to a roughly 358 million year-old calcium carbate accumulation that contains well preserved corals, brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoids, and ostracods--among other major groups of invertebrate animals. Middle Triassic Ammonoids From Nevada: Travel to a world-famous fossil locality in the Great Basin Desert of Nevada, a specific place that yields some 41 species of ammonoids, in addition to five species of pelecypods and four varieties of belemnites from the Middle Triassic Prida Formation, which is roughly 235 million years old; many paleontologists consider this specific site the single best Middle Triassic, late Anisian Stage ammonoid locality in the world. All told, the Prida Formation yields 68 species of ammonoids spanning the entire Middle Triassic age, or roughly 241 to 227 million years ago. Late Miocene Fossil Leaves At Verdi, Washoe County, Nevada: Explore a fascinating fossil leaf locality not far from Reno, Nevada; find 18 species of plants that prove that 5.8 million years ago this part of the western Great Basin Desert would have resembled, floristically, California's lush green Gold Country, from Placerville south to Jackson. Fossils Along The Loneliest Road In America: Investigate the extraordinary fossil wealth along some 230 miles of The Loneliest Road In America--US Highway 50 from the vicinity of Eureka, Nevada, to Delta in Millard County, Utah. Includes on-site images and photographs of representative fossils (with detailed explanatory text captions) from every geologic rock deposit I have personally explored in the neighborhood of that stretch of Great Basin asphalt. The paleontologic material ranges in geologic age from the middle Eocene (about 48 million years ago) to middle Cambrian (approximately 505 million years old). Fossil Bones In The Coso Range, Inyo County, California: Visit the Coso Range Wilderness, west of Death Valley National Park at the southern end of California's Owens Valley, where vertebrate fossils some 4.8 to 3.0 million years old can be observed in the Pliocene-age Coso Formation: It's a paleontologically significant place that yields many species of mammals, including the remains of Equus simplicidens, the Hagerman Horse, named for its spectacular occurrences at Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument in Idaho; Equus simplicidens is considered the earliest known member of the genus Equus, which includes the modern horse and all other equids. Field Trip To A Vertebrate Fossil Locality In The Coso Range, California: Take a cyber-visit to the famous bone-bearing Pliocene Coso Formation, Coso Mountains, Inyo County, California; includes detailed text for the field trip, plus on-site images and photographs of vertebrate fossils. Fossil Plants At Aldrich Hill, Western Nevada: Take a field trip to western Nevada, in the vicinity of Yerington, to famous Aldrich Hill, where one can collect some 35 species of ancient plants--leaves, seeds and twigs--from the Middle Miocene Aldirch Station Formation, roughly 12 to 13 million years old. Find the leaves of evergreen live oak, willow, and Catalina Ironwood (which today is restricted in its natural habitat solely to the Channel Islands off the coast of Southern California), among others, plus the seeds of many kinds of conifers, including spruce; expect to find the twigs of Giant Sequoias, too. Fossils From Pleistocene Lake Manix, California: Explore the badlands of the Manix Lake Beds on California's Mojave Desert, an Upper Pleistocene deposit that produces abundant fossil remains from the silts and sands left behind by a great fresh water lake, roughly 350,000 to 19,000 years old--the Manix Beds yield many species of fresh water mollusks (gastropods and pelecypods), skeletal elements from fish (the Tui Mojave Chub and Three-Spine Stickleback), plus roughly 50 species of mammals and birds, many of which can also be found in the incredible, world-famous La Brea Tar Pits of Los Angeles. Field Trip To Pleistocene Lake Manix, California: Go on a virtual field trip to the classic, fossiliferous badlands carved in the Upper Pleistocene Manix Formation, Mojave Desert, California. It's a special place that yields beaucoup fossil remains, including fresh water mollusks, fish (the Mojave Tui Chub), birds and mammals. Trilobites In The Nopah Range, Inyo County, California: Travel to a locality well outside the boundaries of Death Valley National Park to collect trilobites in the Lower Cambrian Pyramid Shale Member of the Carrara Formation. Ammonoids At Union Wash, California: Explore ammonoid-rich Union Wash near Lone Pine, California, in the shadows of Mount Whitney, the highest point in the contiguous United States. Union Wash is a ne plus ultra place to find Early Triassic ammonoids in California. The extinct cephalopods occur in abundance in the Lower Triassic Union Wash Formation, with the dramatic back-drop of the glacier-gouged Sierra Nevada skyline in view to the immediate west. A Visit To The Fossil Beds At Union Wash, Inyo County California: A virtual field trip to the fabulous ammonoid accumulations in the Lower Triassic Union Wash Formation, Inyo County, California--situated in the shadows of Mount Whitney, the highest point in the contiguous United States. Ordovician Fossils At The Great Beatty Mudmound, Nevada: Visit a classic 475-million-year-old fossil locality in the vicinity of Beatty, Nevada, only a few miles east of Death Valley National Park; here, the fossils occur in the Middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone at a prominent Mudmound/Biohern. Lots of fossils can be found there, including silicified brachiopods, trilobites, nautiloids, echinoderms, bryozoans, ostracodes and conodonts. Paleobotanical Field Trip To The Sailor Flat Hydraulic Gold Mine, California: Journey on a day of paleobotanical discovery with the FarWest Science Foundation to the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada--to famous Sailor Flat, an abandoned hydraulic gold mine of the mid to late 1800s, where members of the foundation collect fossil leaves from the "chocolate" shales of the Middle Eocene auriferous gravels; all significant specimens go to the archival paleobotanical collections at the University California Museum Of Paleontology in Berkeley. Early Cambrian Fossils In Western Nevada: Explore a 518-million-year-old fossil locality several miles north of Death Valley National Park, in Esmeralda County, Nevada, where the Lower Cambrian Harkless Formation yields the largest single assemblage of Early Cambrian trilobites yet described from a specific fossil locality in North America; the locality also yields archeocyathids (an extinct sponge), plus salterella (the "ice-cream cone fossil"--an extinct conical animal placed into its own unique phylum, called Agmata), brachiopods and invertebrate tracks and trails. Fossil Leaves And Seeds In West-Central Nevada: Take a field trip to the Middlegate Hills area in west-central Nevada. It's a place where the Middle Miocene Middlegate Formation provides paleobotany enthusiasts with some 64 species of fossil plant remains, including the leaves of evergreen live oak, tanbark oak, bigleaf maple, and paper birch--plus the twigs of giant sequoias and the winged seeds from a spruce. Ordovician Fossils In The Toquima Range, Nevada: Explore the Toquima Range in central Nevada--a locality that yields abundant graptolites in the Lower to Middle Ordovician Vinini Formation, plus a diverse fauna of brachiopods, sponges, bryozoans, echinoderms and ostracodes from the Middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone. Fossil Plants In The Dead Camel Range, Nevada: Visit a remote site in the vicinity of Fallon, Nevada, where the Middle Miocene Desert Peak Formation provides paleobotany enthusiasts with 22 species of nicely preserved leaves from a variety of deciduous trees and evergreen live oaks, in addition to samaras (winged seeds), needles and twigs from several types of conifers. Early Triassic Ammonoid Fossils In Nevada: Visit the two remote localities in Nevada that yield abundant, well-preserved ammonoids in the Lower Triassic Thaynes Formation, some 240 million years old--one of the sites just happens to be the single finest Early Triassic ammonoid locality in North America. Fossil Plants At Buffalo Canyon, Nevada: Explore the wilds of west-central Nevada, a number of miles from Fallon, where the Middle Miocene Buffalo Canyon Formation yields to seekers of paleontology some 54 species of deciduous and coniferous varieties of 15-million-year-old leaves, seeds and twigs from such varieties as spruce, fir, pine, ash, maple, zelkova, willow and evergreen live oak High Inyo Mountains Fossils, California: Take a ride to the crest of the High Inyo Mountains to find abundant ammonoids and pelecypods--plus, some shark teeth and terrestrial plants in the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale, roughly 325 million years old. Field Trip To The Copper Basin Fossil Flora, Nevada: Visit a remote region in Nevada, where the Late Eocene Dead Horse Tuff provides seekers of paleobotany with some 42 species of ancient plants, roughly 39 to 40 million years old, including the leaves of alder, tanbark oak, Oregon grape and sassafras. Fossil Plants And Insects At Bull Run, Nevada: Head into the deep backcountry of Nevada to collect fossils from the famous Late Eocene Chicken Creek Formation, which yields, in addition to abundant fossil fly larvae, a paleobotanically wonderful association of winged seeds and fascicles (bundles of needles) from many species of conifers, including fir, pine, spruce, larch, hemlock and cypress. The plants are some 37 million old and represent an essentially pure montane conifer forest, one of the very few such fossil occurrences in the Tertiary Period of the United States. A Visit To The Early Cambrian Waucoba Spring Geologic Section, California: Journey to the northwestern sector of Death Valley National Park to explore the classic, world-famous Waucoba Spring Early Cambrian geologic section, first described by the pioneering paleontologist C.D. Walcott in the late 1800s; surprisingly well preserved 540-510 million-year-old remains of trilobites, invertebrate tracks and trails, Girvanella algal oncolites and archeocyathids (an extinct variety of sponge) can be observed in situ. Petrified Wood From The Shinarump Conglomerate: An image of a chunk of petrified wood I collected from the Upper Triassic Shinarump Conglomerate, outside of Dinosaur National Monument, Colorado. Fossil Giant Sequoia Foliage From Nevada: Images of the youngest fossil foliage from a giant sequoia ever discovered in the geologic record--the specimen is Lower Pliocene in geologic age, around 5 million years old. Some Favorite Fossil Brachiopods Of Mine: Images of several fossil brachiopods I have collected over the years from Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic-age rocks. For information on what can and cannot be collected legally from America's Public Lands, take a look at Fossils On America's Public Lands and Collecting On Public Lands--brochures that the Bureau Of Land Management has allowed me to transcribe. In Search Of Vanished Ages--Field Trips To Fossil Localities In California, Nevada, And Utah--My fossils-related field trips in full print book form (pdf). 98,703 words (equivalent to a medium-size hard cover work of non-fiction); 250 printed pages (equivalent to about 380 pages in hard cover book form); 27 chapters; 30 individual field trips to places of paleontological interest; 60 photographs--representative on-site images and pictures of fossils from each locality visited. United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 264-J: Fossils Birds From Manix Lake California, by Hildegarde Howard. United States Geological Survey Bulletin 1928: Stratigraphy of the Lower And Middle(?) Triassic Union Wash Formation, East-Central California by Paul Stone, Calvin H. Stevens, and Michael J. Orchard. United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 483-F: An Unusual Lower Cambrian Trilobite Fauna From Nevada by Allison R. Palmer. United States Geological Survey Bulletin 1527: Age Of The Coso Formation, Inyo County, California by C. R. Bacon, D. M. Giovannetti, W. A. Duffield, W. A. Dalrymple and R. E. Drake. |